Last month, the Dutch government deployed what some see as the nuclear option in efforts to tame banking compensation culture - bonus caps. Its new banking code will restrict bonuses for Dutch bank directors to the equivalent of a year's salary. Pay may not be the most important bit of banking in need of reform, but it is the most visible and most immediately vulnerable to political action.

Given wholesale banks' reluctance to move boldly on pay by themselves - indeed, with evidence of their slipping back into the old ways - such action is starting to warm up. Tougher capital requirements and prudential regulation are more likely to prevent a repeat of the banking crisis. But the item topping the agenda at the G-20 Pittsburgh banking summit (yet to take place as this issue went to press) was 'corporate governance and compensation practices'. Governments know that acting on bonuses offers their best chance of a quick win for electoral consumption.

With opposing views from the US and Europe on the imposition of actual bonus caps, the G-20 will probably stop short of demanding a limit on individual payouts and compromise on capping the total bonus pool relative to a bank's capital or performance.

The organisation doing the legwork for the G-20 is the Financial Stability Board (FSB), the beefed-up group of national financial authorities that used to be the Financial Stability Forum. "Compensation is now fully in the realm of supervisors," declared Mario Draghi, FSB chairman and governor of the Bank of Italy, speaking before the summit. "It used to be they were told it was a private contract. It is now quite clear that when compensation is not aligned with risk-taking incentives, regulators have the right to have their say."

Common ground

Though there is little consensus, even among regulators themselves, over the extent to which bank remuneration should be regulated, some more-or-less agreed principles are crystallising. It is clear that, from now on, bonuses will have to be more firmly tied to actual performance.

During the summer, New York state attorney general Andrew Cuomo articulated the public and political mood in the title of his report on bonus payments by nine big US recipients of Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) funds. Called No rhyme or reason: The heads I win, tails you lose bank bonus culture, it showed starkly how the excess of 2008 bonus payments over earnings (or losses) at six banks belied their claims to link pay to performance.

Despite losses of more than $27bn apiece, Citigroup paid $5.33bn and Merrill Lynch $3.6bn in bonuses. Goldman Sachs paid out $4.8bn against earnings of $2.3bn, and both Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase were singled out for similar imbalances. All received substantial TARP funding.

"Compensation packages should be designed to promote long-term, sustainable growth and actual increases in value," said Mr Cuomo. "This would drive firms towards decision-making that promotes long-term actual growth and performance rather than the dangerous combination of short-term booked profits and blow-up deferral caused by the current bonus culture."

Sounder and more principled bonus systems, he went on, would make firms less susceptible to the poaching of their employees and the one-way ratchet bidding wars that harmed the entire industry. Mr Cuomo accepted that a private sector solution would be the most appropriate. But he warned that if the market could not provide a remedy, then the federal government should.

Public perceptions

Elsewhere, politicians, the media and the public are mutually reinforcing each other's outrage along similar lines, fuelled by reports of large bonus promises for new hires by banks in receipt of government funds. Outside the Anglo-Saxon world, however, there is little appetite for a market-driven resolution. And even Anglo-Saxon free marketeers are less inclined to take ideological issue with regulation itself than simply to insist it will be pointless.

"No one should kid themselves that tinkering with bankers' bonuses makes a similar crisis any less or any more likely in the future," argues Nicholas Boys Smith, consultant director of the right-of-centre UK think tank, Reform. "It may be politically right. It may even be just. It is economically irrelevant."

Mr Boys Smith points out that incentive schemes at some of the worst affected banks successfully encouraged long-term employee share ownership. This was particularly the case at Bear Sterns and Lehman Brothers, to little avail, he says.

Be that as it may, new compensation rules for bigger banks in general and investment banks in particular are inevitable - indeed, they have already been drawn up in some countries. Exactly what form they will take in other jurisdictions, and how universally they will apply, remains to be seen.

Presumably, most of the G-20 nations, encompassing the world's largest banks, will bend the knee to the broad-brush template laid down by the FSB at the G-20's request. If Mr Cuomo stressed the need to make bonus incentives more long term by nature - with more equity content - the FSB wants to ensure that employees' compensation takes account of the risks they take on behalf of the firm.

As it points out, two employees may generate the same short-run profit while exposing the firm to entirely different amounts of risk. The compensation system should not treat them both in the same way, the FSB maintains. The size of the bonus pool should reflect the overall performance of the firm and, since the profits and losses of different activities tend to be realised over different periods of time, compensation should be staggered accordingly. Payments should not be finalised over short periods for risks that are realised over long periods. And compensation of back-office and risk-control staff shouldn't be influenced by front office personnel.

The FSB principles for "sound compensation practices" at significant financial institutions have three main planks: aligning compensation with prudent risk-taking; ensuring this is controlled and monitored at board level; and having it all under the watchful eye of regulators and other 'stakeholders'. The FSB undertook to put more flesh on these bones at Pittsburgh.

The FSB has acknowledged one key fact of life here - that none of this will work unless it is implemented and enforced internationally. The alternative will be a form of pay cheque arbitrage in which the banking supertalent will migrate to less regulated jurisdictions.

One rule wanted

That point is made unremittingly by banks themselves. While the industry seems incapable of acting unilaterally, most of the players affected would welcome internationally imposed rules that kept the playing field level - whatever they were. Some form of less-than-completely-bland agreement at the G-20 would be useful to them, but individual national implementation would be crucial, and far from guaranteed.

"We are very keen on an agreement, but we also need agreement [for all G-20 nations] to implement any measures in the same way and to an equitable timetable," says Angela Knight, CEO of the British Bankers' Association. Third-world non-governmental organisations will tell you what invariably happens with international conference pledges, she adds. "You get the handshakes and the photos, but then you get significantly less than was promised."

Some countries, such as the UK, the Netherlands and France, have not waited for the G-20 but are already going it alone, hoping that the rest of the world will catch up. And already there are differences in their approaches that don't auger well for future international harmonisation of rules, notably in their attitude to caps.

The UK, conscious of the financial services sector's prominent role in its economy, has led the charge in regulatory response. In August, its Financial Services Authority (FSA) published the final version of its remuneration code of practice for banks. It was somewhat watered down from the original March draft, and will no longer apply to non-UK firms, but only the 26 largest UK banks and building societies.

The code highlights the concepts of deferral and, by implication, clawback, if bonus-generating transactions ultimately turn sour. The original draft laid down three principles. An employee's fixed pay element should be sufficient for banks to be able not to pay a bonus in loss-making years. Payment of at least two-thirds of any bonus should be deferred for at least three years. And a significant proportion of this variable pay element should be linked to future performance of the firm and, if practicable, the employee's business unit.

These principles were so-called evidential provisions, meaning that non-compliance with them would be evidence of a breach of the rules. In the FSA's final version they have been downgraded from principles to guidance - statements of good practice. They have been replaced by a single principle, that firms must design and operate their remuneration policies and practices to be consistent with and to promote effective risk management.

Guarantees back

If anything militates against links to performance, risk and the long term, it is the guaranteed bonus. Used to poach new employees or hang on to existing ones - in the form of the retention bonus - it looked as if it was dying out as banks struggled to survive last year. Now it appears to be staging a comeback on both sides of the Atlantic, often in multi-year form. While not turning its face against them completely, the FSA has said that guarantees of anything over one year are "unlikely to be consistent with effective risk management".

The rules come into effect in January, which may prompt a pre-deadline wave of extravagant bonus promises in the old fashion. They will be policed on the basis of "comply or explain", though the FSA retains the ultimate sanction of ordering offenders to hold more capital, which would eat into profits and, therefore, the pool available for distribution. Lest London find itself out on a limb in terms of international regulatory competition, it has promised to review the rules in a year's time. It is also working alongside the UK government to persuade other jurisdictions to adopt a similar regime.

"The question is to what extent will the FSA want to roll up its sleeves and use the ultimate sanction?" asks Christopher Page, London-based associate partner, people services, at KPMG. "It's a moot point."

Nonetheless, Mr Page believes that the comply-or-explain approach has merit. "In the US, they tend to legislate," he explains. "But once you start to legislate, the first thing advisers do is to find ways around it. Comply and explain is just that - why haven't you complied?"

The UK has also published a report on corporate governance in banks, the Walker Review. Commissioned by prime minister Gordon Brown, it includes a number of recommendations on remuneration, which are more prescriptive than the FSA code.

Former investment banker Sir David Walker zeroed in on the fact that direct board oversight of pay is generally restricted to that of the directors themselves. While some bank employees earn many times more than board members, their packages are nominally the responsibility of the human resources department but, in practice, often under the control of heads of business units.

So Sir David wants to extend the remit of banks' remuneration committees (remcos) to all highly paid employees. He also recommends disclosure of the total pay packages for these employees, not by name but in bands.

Held to account

Corporate governance is the stamping ground of shareholders, which raises the question of what they have, or have not, been doing to rein in the bonus culture. "This debate is not about whether bonuses are good or bad," says Mark Thompson, associate director in the rewards practice at management consultants Hay Group. "They are good - they are useful in retaining people and form a direct link between achievement and reward. But in banking they have turned into a market arms race. And shareholders need to take more of a front seat in holding these companies to account."

Peter Montagnon, director of investment affairs at the Association of British Insurers, defends shareholders' apparent lack of action. "We get very little information and we have very limited powers in this area," he says. "In the UK we are never able to vote on anything other than board pay. But we do want to be sure that boards are on top of this issue."

In a world where revenues can fluctuate widely and pay forms a large part of total costs, companies would clearly have problems if they were tied to high levels of fixed pay, he says. "So we need to make the existing process of variable pay work better, taking into account risk and the adjusted cost of capital. We will be scrutinising the interplay between risk and remuneration more carefully than before."

Mr Montagnon approves of the Walker proposal for publication of banded pay and the extension of the remco remit. He is concerned, however, about forcing deferral of too large a portion of remuneration which, he says, leads to overlarge buyouts - when banks poach staff by offering to make up any forfeited deferred compensation. For that reason, he wants guaranteed bonuses to be stopped, allowing pay deals to be "parked" with the previous employer and paid out at the end of the deferral period if all goes well.

He also argues against hamstringing what are now government-owned banks by discriminating against their ability to hire talent. "It's very important that they flourish and become worth a lot of money before they are sold for the benefit of the taxpayer. Impose uncompetitive discrimination and we'll all pay."

Bonus acceptance: Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein, seen here in a TARP meeting earlier this year, has recently come out in favour of certain restrictions to bonus structures

General agreement

If not exactly consensus, there is an emerging acceptance of the broad themes in future bonus structures. Even Goldman Sachs CEO Lloyd Blankfein recently saw politically fit to publicly embrace higher equity content, deferral and clawback, and linkage to company-wide performance. He also called for a ban on multi-year guaranteed contracts. The outstanding issue for now is to cap or not to cap.

The most vociferous call for individual caps has come from France, supported by Germany, though they have stopped short of unilateral action for competitive reasons. The US does not favour them while the UK, initially hostile, has gone quiet on the subject recently. The FSA has said that it is not its job to implement a pay policy, and that it is up to shareholders to influence how much staff are paid.

Let managers manage

The ABI's Mr Montagnon does not favour formal capping or, indeed, any excessive shift from variable to fixed pay. "Management has got to have the right to manage," he says.

Others warn that official caps will have a legislative effect, encouraging the search for alternative structures - bonuses that are not bonuses. Some banks have experimented with 'forgivable loans', 'loans' that don't have to be paid back.

"If government starts regulating the amounts that banks can pay, it will be a complete disaster," believes Hay Group's Mr Thompson. "Every time a government tries to do something on pay, it goes in the opposite direction. When the UK introduced income policies in the 1970s, it resulted in executive pensions so generous that they are still complaining about them now."

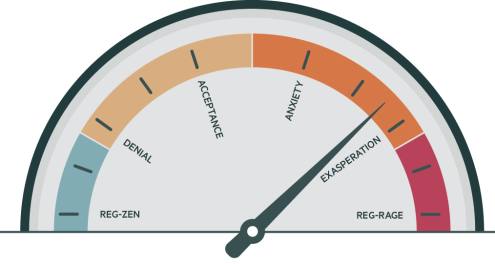

Caps may not even hit the right targets. The new Dutch rules, for example, don't apply to well-paid traders or anyone else below board level. What they do say, however - and this should unsettle bankers everywhere - is that remuneration policy must take into account "society's acceptance".

Social utility and acceptance is beginning to inform the public view of bankers and banking. Even the FSA chairman, Adair Turner, recently questioned whether the financial sector's size and some of its products were "socially useful".

When the debate moves onto that turf, it is time for bankers to take public perceptions very seriously indeed. Given that bonuses are in the front rank of those perceptions, they seem like a good place for banks to start cleaning up their act.