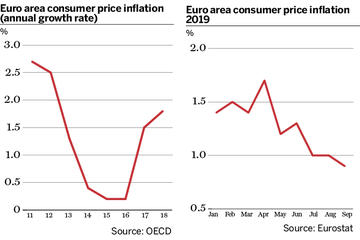

For an institution that is no stranger to crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) is enduring a particularly difficult year. Trade tensions between the US and China have hit the euro area economy hard, while the inflation rate is dropping to multi-year lows. The ECB’s decision to launch a monetary stimulus package in September 2019, to counter these problems, is expected to offer modest support at best. But a return to unorthodox easing measures has also ignited ideological divisions along the euro area’s monetary policy fault lines.

All of this has unfolded less than a year after the end of the ECB’s last round of quantitative easing. It also comes as Christine Lagarde, the former head of the International Monetary Fund, takes over the ECB presidency. Her predecessor, Mario Draghi, who had held the position since 2011, has left an indelible mark on the euro area’s recent economic history. He is also leaving Ms Lagarde with the unenviable – if inevitable – task of bridging the divisions between the region’s monetary policy hawks and doves.

Expansionary fiscal policies

In order to close the divide, Ms Lagarde is faced with the task of convincing European governments to pursue expansionary fiscal policies. This is no small feat, but many feel it would help to spur economic growth and alleviate the pressure that has mounted on the central bank over the past decade. Through the shortcomings of the euro area’s fiscal and monetary architecture, the ECB has been the only body capable of supporting the eurozone economy over this period.

And though it has at times pursued unorthodox measures – which have led to distortions in asset markets, for instance – it has at least been decisive in its efforts to support the economy. “The burden to try to support growth has fallen very heavily on the ECB. It has been pretty much the only game in town,” says Lee Hardman, a currency analyst at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group (MUFG) in London.

Nevertheless, this situation has led to an over-reliance on monetary policy tools – from quantitative easing to negative interest rates – to address the euro area’s economic ills. The absence of corresponding fiscal stimulus or, in some cases, structural reforms, has led to an uneven policy terrain that has exposed the ECB to severe criticism. The latest package of easing measures is no exception; it has, for example, provoked an unparalleled level of dissent from within the bank itself.

“The level of opposition to the latest stimulus package is quite profound. It is coming not only from the governors but also from some executive board members. In the past, Mr Draghi has had a strong majority in the executive board. He didn’t this time,” says Shahin Vallée, senior fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations.

Sabine Lautenschläger, a German representative on the six-member executive board of the ECB, resigned in late September in part due to her opposition to the monetary policy being pursued, according to the Financial Times. Additionally, in a highly unusual intervention, the central bank governors of Germany, France, Austria and the Netherlands all publicly voiced their opposition to various components of the stimulus package. Meanwhile, in October, six former eurozone central bank governors issued a two-page memorandum criticising the ECB’s policy stance.

Countering regional slowdown

As Mr Vallée notes, the package was introduced to counter Europe’s accelerating economic slowdown. But it also stemmed from a desire by Mr Draghi to ease Ms Lagarde’s leadership transition. By launching this stimulus, it leaves Ms Lagarde with a predetermined monetary policy direction during the opening months of her tenure. In theory this should have been helpful, but it may also work to her detriment.

“There is a danger that Mr Draghi has overreached. By trying to make things easier for Ms Lagarde, he may have made her life more complicated because she is going to inherit a board and council that is a lot more fractured. He may have created a minefield for her. She will be under tremendous pressure by the dissenters to [dial down] his stimulus package,” says Mr Vallée.

Under the scheme, the ECB cut its deposit rate by 10 basis points to -0.5% and commenced an open-ended return to quantitative easing with net asset purchases of €20bn per month. The banking sector has secured relief through the introduction of a tiered deposit scheme that diminishes the amount of excess liquidity subject to negative interest rates. Under the ECB’s package, this applies to reserves up to a value six times greater than the minimum requirement (the total reserve requirements for euro area banks with the ECB stand at about €113bn).

The central bank has also improved conditions for targeted longer term refinancing operations (TLTRO), essentially cheap loans issued to banks by the ECB, which include extending their maturity from two years to three years. Collectively, these measures are designed to stimulate economic growth and stoke inflation across the euro area. But it remains unclear what impact they will have on the region’s banks and to what extent they will facilitate increased lending to the real economy.

Bad for banks?

Superficially, the deepening of a negative interest rate environment is a less favourable outcome for the banking sector. “The broad picture is that Mr Draghi and the council of governors decided that euro area banks will have to bear negative rates for longer, without any deadline, until inflation edges close to 2%,” says Olivier Panis, vice-president and senior credit officer at rating agency Moody’s.

Mr Panis believes the implementation of the deposit tiering scheme is a sign the ECB recognises that banks’ profitability will start to suffer moving forward as lower interest rates and slowing growth begin to take their toll. “The banks will find it hard to increase their lending in a slowing economy,” he says. “In addition, most of the large euro area countries have rid themselves of a large proportion of their bad legacy loans so it is difficult to anticipate a lower cost of risk. As a result, European lenders now lack the tools to counterbalance the impact of lower interest rates going forward."

The deposit tiering scheme itself will mainly favour large banks from the north of the euro area. French and German institutions in particular have the most to gain. Of the roughly €1900bn of banks’ excess liquidity sitting in the ECB, about €1100bn stems from lenders from the two core countries, according to data from Moody’s. However, the mechanism is expected to deliver aggregate savings of between €2bn to €3bn per year, according to most estimates, for these lenders and others that have excess liquidity above the ECB’s threshold.

Meanwhile, the introduction of improved TLTRO terms should offer some relief to smaller lenders on the periphery of the euro area. Under the scheme, banks that meet specific criteria will be able to secure loans from the ECB at a rate of -0.5% for three years. Though uptake was low in the September 2019 TLTRO auction – the first of its kind under the new package – there is an expectation that euro area banks will be more inclined to secure the loans in the December auction, once all of the easing measures are in place.

Blunt instruments

Though the ECB’s stimulus package offers mixed blessings for eurozone banks, it underscores the institution’s willingness to act in times of uncertainty. Nevertheless, the days of the central bank being able to offer effective interventions in support of euro area growth may be coming to an end. It is unclear whether the ECB’s policies have reached a point of diminishing returns, for instance, given the full range of monetary policy measures deployed in the preceding decade.

“The fact is that we have reached a point where monetary policy is becoming more problematic as the side effects of its implementation manifest,” says Oliver Rakau, chief German economist at Oxford Economics. “Negative deposit rates could be cut further but there isn't that much space. Quantitative easing could be expanded but the yields on government bonds are so low that additional stimulus would lack power. The boundaries of monetary policy are being reached.”

Indeed, the ECB’s latest measures are seen as a last roll of the dice, meaning that any worsening of the economic operating environment will leave the institution exposed. “The ECB has now put all its chips on the table, at least in terms of the different tools it can use,” says Bert Colijn, senior economist at Dutch lender ING. “So there isn’t all that much more that can be done if the economic situation deteriorates. It leaves the institution somewhat vulnerable if it wants to push back with anti-cyclical policies in the event of a recession.”

The danger is that economic growth is cooling swiftly across the euro area. The IMF has slashed its 2019 growth forecast for the region to 1.2%, while its prediction for 2020 is only marginally better, at 1.4%. A pronounced slowdown in Germany, off the back of weaker industrial production and slowing global trade, is playing a sizeable role in this gloomier outlook. Further dents to euro area growth – US president Donald Trump’s threat to impose tariffs on German automakers being a case in point – now present a grave threat.

“The problem for the ECB is that it can implement monetary easing but it has no control over exogenous threats to the eurozone economy, such as rising global trade tensions and the prospect of US auto tariffs on the EU,” says MUFG’s Mr Hardman. “The latest eurozone data has continued to disappoint. [There is a heightened] risk of the economy stagnating or falling into recession. It is difficult to see right now where a positive reversal could take place.”

Pressure for stimulus

With few options left in its monetary toolbox, the ECB faces a situation where it has more or less exhausted its capacity to respond. Consequently, pressure is building on euro area governments to enact fiscal stimulus measures to prevent a recession. Mr Draghi, in one of his final press conferences, noted that it was “high time” for fiscal policy to play a role in shoring up the region’s economy. The challenge facing Ms Lagarde is to translate these pleas for fiscal support into reality. “The expectation is that she will be more active and be more effective at pressuring governments to loosen fiscal policy. She has excellent contacts and they could be used to her advantage,” says Mr Hardman.

Nevertheless, this process will not be straightforward. For one, the euro area economies with the fiscal space to support stimulus are, in some cases, reluctant to do so. “We now need a better mix of structural fiscal policies in the current interest rate environment. Primarily, this should come from the countries with structural surpluses, including Germany, the Netherlands and Austria,” says Mr Rakau.

Second, eurozone fiscal discipline rules remain strict and will require amendments if a meaningful and coordinated stimulus package is to be deployed in the future. For many observers, the key to unlocking fiscal change in the eurozone lies with Germany. “If we want fiscal expansion, the current [eurozone] rules won’t work,” says Mr Vallée. “The only scenario in which these discussions are going to work is if Germany confronts them. I am not optimistic that Germany is prepared to move [towards fiscal stimulus]. Europe will not move unless Germany moves. There is a tremendous responsibility on the part of Germany.”

Maintaining black zero

For now, the German authorities remain committed to a self-imposed objective of a balanced budget, known as ‘black zero’. In addition, the country faces a constitutionally imposed requirement, known as the debt break, that prohibits the 16 federal regions from running deficits while the federal administration is limited to a structural deficit of 0.35%. But with Germany now facing the prospect of a technical recession and as wider euro area problems begin to mount up, there is growing pressure both inside and outside Berlin for fiscal change.

“The fact that Germany is currently experiencing a slowdown could be a silver lining to this story because it could reboot the discussion around black zero and whether fiscal spending should be employed as a counter-cyclical measure,” says ING’s Mr Colijn.

This may help Ms Lagarde, and others, in the push to generate a fiscal response to the euro area’s woes. But it is not guaranteed. The longer the delay, the greater the challenge for the ECB as it incurs the wrath of savers in the northern and core economies losing out from the continuation of the negative interest rate environment. Not only does this dynamic undermine unity within the eurozone but it is also likely to exacerbate tensions in a divided central bank.

“What I tell people in the north of Europe who are upset about the ECB’s approach is that the best way to avoid negative interest rates is to empower fiscal policies in Europe,” says Mr Vallée. “Northern Europeans can’t have it both ways: refuse fiscal expansion and then complain that the ECB is doing a bad job. The situation we are in is completely unsustainable. I am not optimistic in terms of seeing signs of changes but I don’t think the current situation can endure.”

Need for action

The question of when national governments may act has become critical. The introduction of tax cuts in France and the Netherlands, alongside a recently agreed spending boost for the green economy in Germany, will offer some support. With the eurozone’s forward-looking indicators appearing particularly weak, according to research from ING, there is a growing need for action. A leaked European Commission discussion paper from early October, which was drafted in preparation for an EU summit in the middle of the month, highlighted the need for pre-emptive fiscal stimulus.

Despite these signals, the prospects for a coordinated fiscal response from eurozone members is still some way off. Oxford Economics’ Mr Rakau says: “We don’t see a coordinated fiscal loosening occurring in the eurozone because the economic situation isn’t bad enough yet for those types of measures. This would change if there were larger spillovers in industrial weaknesses that hit domestic demand and employment. At that point, the political picture would change.”

Until this changes, the eurozone’s economic prospects will remain far from certain. And as the downside risks to the global economy grow in size and complexity, the need for a balanced monetary and fiscal policy environment in the euro area has never been greater. Ms Lagarde’s tenure as ECB president may be starting with a continuation of monetary stimulus measures, and a deeply divided central bank, but if she can play to her strengths and push for a fiscal response from member states, she might find a way to better prepare the euro area for the next global economic storm.