Few areas of banking hold as much promise as wealth management and private banking. Unfortunately, however, few areas are in such a state of flux either.

The appeal for bankers is, evidently, that rich people have more money to invest and are more willing to pay for advice than the less well off. The size of the market is also colossal (see box).

Editor's choice

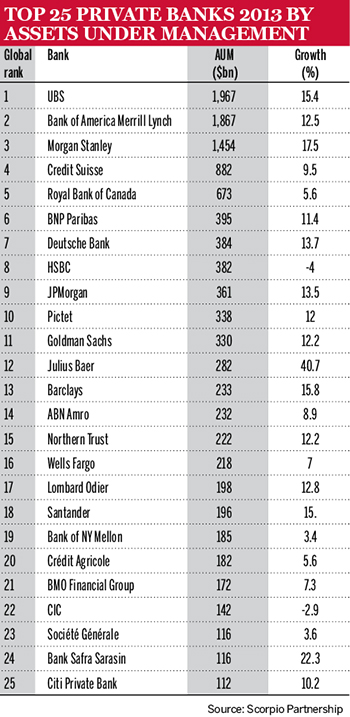

So with the financial crisis behind them and stock markets surging all over the world, private banks are rebounding. In 2014, Citi Private Bank, based in New York, increased its global assets under management by 5% in 2014, to $374bn. In the same year, the wealth management business of Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) contributed 12% to the bank's total earnings. RBC, Canada’s biggest bank, has the fifth largest private banking business in the world (see chart).

Key requirements

Officials at Citibank and RBC, as well as those at Spain’s Santander and BBVA – both of which reported positive results in their wealth management operations last year – agree that some key requirements are needed to succeed in private banking.

They are unanimous in stressing the importance of having a clearly segmented customer base. In RBC’s case, this means a focus on high-net-worth (HNW) and ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) clients with financial assets (excluding their businesses and their homes) of more than $1m and $30m, respectively. At Citi Private Bank, the focus is exclusively on UHNW clients with assets of more than $25m.

Another determinant of success is providing and delivering on assurances to preserve client confidentiality, according to Alfonso Sanchez, the head of Santander’s private bank in Mexico. However, rules eroding bank secrecy laws are limiting banks' abilities to provide such guarantees.

Peter Charrington, global head of Citi Private Bank, believes that Citi's overall strengths and its reputation are an important factor in the success of its wealth management business. He cites Citi’s extensive international retail branch network, its local management teams, and its policies and procedures for know your customer and customer due diligence as key draws for Citi Private Bank. “We have seen examples of other firms around the world that have not been [following customer due diligence procedures] and the issues they have come across,” he says.

For instance, the UK’s HSBC agreed to pay $1.9bn in 2012 to settle charges that it failed to catch drug trafficking money being laundered through its US bank. The lender has since pulled out of several developing countries, partly, it claims, to minimise the risk of future money laundering compliance problems. By contrast, Mr Charrington says: “None of our business is shrinking in any region around the world.” (Citi’s private banking, outside of the US, is primarily based in Hong Kong, Singapore, Mexico and Brazil.)

Meanwhile other attractions of private banking are that in a low-interest-rate environment, private banking, as it is a fee-earning business, is a way to boost bank profits. Regulatory capital requirements, including those laid down by Basel III, are also less onerous in private banking than they are for other areas of banking, such as lending. Additionally, private banking does not strain a bank’s balance sheet, as wealthy clients tend to leave more money in a bank, in investments and deposits, than they borrow.

New challenges

But for all the advantages, private banking – as traditionally conceived – faces many challenges. Margins are under pressure, while fees are declining across the industry and becoming more transparent.

At the same time, costs are also rising. For instance, big corporate and commercial banks such as Citi now entice their UHNW clients with elaborate services, in addition to offering more standardised investment services and products, covering the likes of the capital markets, portfolio management and trust and estate planning. At Citi Private Bank, additional services include helping a client build an art collection or buy a sports team or a private jet. But such services come with high costs, costs that are hard to measure. However, after substantial investments in technology, much of the 'thinking' when it comes to asset allocation and risk management for rich clients is now done digitally at international banks such as Santander, which helps to cut costs.

The cost of hiring private bankers is also rising, while it is becoming increasingly difficult to find managers, especially in emerging markets, who can combine a high education and training in financial markets with presenting the kind of image preferred by more conservative, older HNW and UHNW clients. “It’s not something that grows on trees,” says one private banker.

A further challenge is that as clients at the top end of the market behave in a manner more akin to institutions, this opens the door for more wealthy clients business to be won by big investment banks, increasing competition over fees and products for traditional wealth managers.

A different kind of competition

The biggest challenge, however, according to those familiar with the industry, is now coming from new competitors from outside banking, who are using technology and offering wealth management services that are radically different – and much cheaper – than those of a traditional private banks.

An example of this can be seen in the clash of cultures between old and new wealth management firms in California. On the one hand, RBC made US media headlines in February buying City National Corp, a US private and corporate bank with a roster of rich celebrities among its clients and a presence in some of the largest US wealth markets. Those include Los Angeles, where the bank is based, and New York and San Francisco. RBC says the deal cost $5.4bn, making it the largest acquisition of a US bank since 2011.

However, in California over the past three or four years, particularly in San Francisco and Silicon Valley, new online firms such as Market Riders and Personal Capital are employing technology to help clients design customised asset portfolios at a fraction of the price charged by traditional wealth managers. In addition to this, two well established US brokerage firms, Vanguard and Charles Schwab, recently launched their own online investment platforms and portfolios. And Schwab, with more than $2000bn in assets under management, is offering digital data and basic investment advice to clients for free throughout 2015.

According to US research company Morningstar, in the past five years US clients have moved $73.6bn of their investments out of actively managed US stock funds (where managers aim to beat the market) and placed $208.8bn in index funds that only try to match the market, but where the fees are about 80% less.

Mark Tuckman, CEO of Market Riders, says: “There is enormous decompression going on at both the fund management level, because of index funds, and at the advice level, because of automated advice tools.”

Personal Capital’s CEO, Bill Harris, estimates that the fees his company charges investors are “about half” those of a traditional wealth management firm. “I think the migration [from traditional banks to new online firms] is inescapable. Everything is being transformed by connectivity," he says.

However, many private bankers are sceptical about the new do-it-yourself firms, and point out that the new online firms have a very different customer base from that of most private banks. Indeed, online firms tend to attract young, highly paid technology employees as well as middle-aged clients planning their retirement, whose investments rarely exceed $1m. But the difference in segments between the old and new models is blurring, according to some within the industry.

Regulatory pressures

Against this background, another source of pressure for traditional wealth management is coming from the new regulatory environment. In the past few years, media attention has focused on the private banking activities of large international banks, with US, European and Latin American regulators and law officials launching numerous investigations over alleged money laundering, tax evasion or US economic sanctions violations.

The turmoil brought about by this increased regulatory scrutiny is particularly evident in Miami, which has become an important hub for the offshore wealth management activities of large international banks, particularly those from Latin America.

David Schwartz, CEO of the Florida International Bankers Association, says one of the consequences of the new regulatory environment is that private bankers are “more wary” and are focusing more on the very wealthy because of increasingly high compliance costs. "It’s a much heavier burden. And as criminals become more sophisticated – and the [compliance] costs become more prohibitive – at a certain point a bank makes the decision [that it is] just going to focus on higher net worth, more profitable customers, even if they are a higher risk... as opposed to the tier of customer that does not yield as much but where the costs of compliance with regulations are the same,” he says. 'This leaves a sort of niche for smaller banks to deal with customers below the high thresholds.”

In the money

In its latest annual report, the Boston Consulting Group estimates that the total financial assets of the world’s wealthy (excluding businesses and homes) amounted to $152,000bn in 2013, 14.6% more than in 2012. North America and western Europe are still the world’s wealthiest regions, while Asia is the fastest growing. Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Middle East and Africa also experienced double-digit growth. However, taking currency devaluations into account in Latin American countries such as Brazil (down 13 %), Argentina (down 37%) and Chile (down 9%), private wealth in Latin America declined in 2013.

Meanwhile, total assets under management (AUM) in the world grew 13% to a record $68,700bn in 2013. In the US, total AUMs amounted to about $30,000bn, almost double the country's entire gross national product (which was $16,500bn at the end of 2014).

The Boston Consulting Group estimates that asset management continues to rank among the most profitable industries in the financial industries. Operating margins, or profits as a percentage of total global net revenues, grew from 37% in 2012 to 39% in 2013, approaching the pre-crisis high of 41%. However, revenues have grown more slowly than assets, partly because of a general shift away from higher margin, more complex and riskier investment products. Moreover, since the crisis, costs have risen faster than revenues. Revenues were 2% higher in 2013 than in 2007, but costs were 6% higher.

RBC's exit

Several private banks are also re-positioning themselves as a result of regulatory issues. One of these is RBC, which over the past 18 months has decided to exit a once-favourable wealth management business in Latin America, closing all its offices in the region along with its international wealth management business in the Caribbean and certain international advisory groups in Canada and the US. In an emailed statement, RBC added that its wealth management business in the region represented only a small component of the bank’s total international private banking business. However, others have claimed that the risks associated with possible money laundering probably did not justify the profits that RBC was making in the region.

The exit came after the US Comptroller of the Currency – which regulates US banks and the US branches of foreign banks – found in 2013 that RBC’s anti-money laundering controls were inadequate, and told the bank to remedy the matter.

The upshot is that RBC is re-focusing its wealth management business back to its traditional markets: Canada, the US, the UK and Asia. "We know we succeed best when we leverage and build on the strengths of RBC’s other businesses. This collaborative approach will remain core to our growth strategy,” says George Lewis, group head of RBC Wealth Management.

Latam attractions

Meanwhile, expanding in the other direction, in 2014 Santander’s private bank in Miami acquired BNP Paribas’s US offshore wealth management business, which services mainly rich Latin American clients. This came in the wake of the French investment bank deciding to pull out of several developing countries after agreeing to pay US regulators a $9bn fine to settle charges of allegedly violating US economic sanctions and anti-money laundering rules.

The Safra banking group, which has its headquarters in Switzerland and a boutique bank in Brazil, was also quick to appoint 12 former RBC managers in Latin America to senior positions at Safra’s brokerage firm in Miami and the Safra National bank of New York.

Other banks that have been ramping up their offshore wealth management business in Miami for HNW Latin Americans include BBVA and Latin America’s largest regional bank, Itaú Unibanco of Brazil. Banco Crédito e Inversiones, Chile’s third biggest bank, is also targeting the HNW offshore segment in Miami following its acquisition in 2013 of the City National Bank of Florida for $883m from Spain’s troubled Bankia group. The deal marked the first major foray by a Chilean bank into the US market.

“We’ve seen that if a player decides to exit the market, there have been many willing suitors stepping up to acquire that business," says Mr Schwartz.