“The question how far this interdependence will continue, how far the Reserve System will be the ultimate hope for the stock market, and how far it is likely that repression instead of inflation of speculative loans will be resorted to, are the problems still to be settled in the course of time”

“If the US and Europe have had to intervene in such a momentous fashion to get credit flowing again, what does that say about the notion of free markets? If the nightmare on Wall Street can only be ended with greater oversight from the Federal Reserve, what does that say about the ideal of deregulation that the West has championed?”

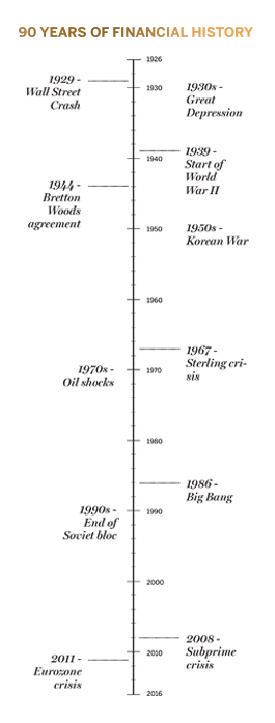

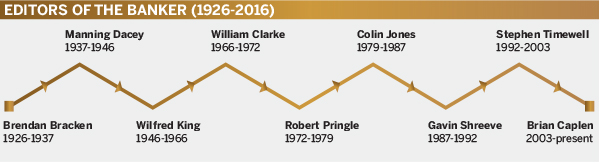

Only the register of language provides much clue that these two paragraphs appeared in the pages of The Banker magazine almost 80 years apart. New York correspondent Henry Parker Willis, writing the first paragraph in December 1929 under the founding editorship of Brendan Bracken, lamented the irresponsible behaviour of the banks that had engaged in margin lending to securities brokers devastated by the Wall Street Crash.

“The banks have undoubtedly plunged into a speculative whirlpool with their eyes open and with thoughtless disregard of consequences. Of course, that raises a question more important than mere analysis of conditions can be: how can American banking be set straight and induced to guide itself by the canons and principles which are essential as demonstrated by past financial appearance?”

Nor were the authorities spared from his critique. The reserve banks had “pursued a fluctuating and insincere policy, sometimes assisting market speculation, and at other times apparently repressing it, but never exerting any general influence toward the establishment of sound canons of banking management”, wrote Mr Willis, who found time for his role as professor of banking at Columbia University in between writing monthly articles for The Banker.

Just weeks after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, investment banking editor Geraldine Lambe, writing the second paragraph, was equally quick to point the finger at regulatory shortfalls: “Fed oversight did not prevent Citigroup’s horrendous losses, just as the Financial Services Authority did not save Northern Rock from disaster.”

Winston Churchill, in whose cabinet Brendan Bracken later served during the Second World War, once spoke of “the long, dismal catalogue of the fruitlessness of experience and the confirmed unteachability of mankind”. Thankfully, he was not describing our magazine, but The Banker has witnessed enough history to see at least some of it repeating. Our editors certainly have long memories – averaging a decade each since Bracken founded the publication in 1926. Banking has changed beyond recognition over the nine editors and 90 years of The Banker, but have lessons been learned from the events covered in our pages?

Darlings and admirers

One obvious change since the 1920s is the globalisation of banking. The Banker was always at the forefront of that trend, including articles on India and South America in its very first edition. Nevertheless, the early years were comparatively parochial, with features on topics such as bankers in England’s West Country and the architectural delights of Westminster Bank’s interiors.

Part of the challenge was simply one of logistics. The majority of the international coverage came from the magazine’s two correspondents based in New York and Paris. This is, of course, a world away from today’s instant communication that allows global coverage at the touch of a button. Over time, the role of cross-border flows has come to play as large a part in the magazine as it has in the financial world itself.

Intriguingly, Mr Willis’s article on the Wall Street Crash contained not a single mention of the international ramifications, even though these proved to be drastic. By the 1960s, the magazine’s fourth editor, William Clarke, became the director-general of the City’s committee on invisible exports, and is credited with being the first journalist to use the word 'Eurodollar'. By September 1982, coverage of the Mexican sovereign debt default carried a decisively international tone: “Quite simply, the stability of the world’s banking system was put at risk as the largest US banks and others scrambled to assemble an emergency bail-out for Mexico.”

Correctly identifying the start of the Latin American debt crisis that was to hang over the global financial system for almost a decade, the article went on to list other countries at risk of default, including Brazil, Argentina, Cuba and Costa Rica. The description of Brazil was especially unflattering toward both debtor and creditors: “The bankers’ ‘darling’ will be transformed back into a troublesome mistress whose expensive lifestyle will again begin to cause the utmost concern.”

For a business that should be rooted in unsentimental hard numbers, banking does seem strewn with tales of inappropriate infatuation. Less than two decades after the Latin American crisis, there were similarly disapproving tones in the magazine’s coverage of the Asian currency devaluations in August 1997. There were clear echoes of the Mexican crisis, “much though Bangkok is loath to admit it”, an editorial suggested.

“The southeast nations (Thailand especially) became so hooked on foreign capital inflows into their stock markets and banking systems that they could not countenance the idea of disappointing their legions of admirers among foreign fund managers and bankers by admitting that their currencies were overvalued,” The Banker team opined.

But the rise of global finance at least provides some positive examples of new opportunities to learn from history. By the time the 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy unleashed the worst financial shock since 1929, it appeared that emerging market sovereigns had learnt the lessons of the 1980s.

“There is general consensus that emerging market sovereigns are fundamentally more resilient after several years of better fiscal management and the build-up of foreign exchange reserves, enabling them to stay on the sidelines of today’s troubled credit markets,” The Banker noted in October 2008.

Unsound, unscientific

Unfortunately, one’s own mistakes always seem to provide a sharper lesson than other people’s mistakes. Hence the sovereign debt crisis of 2010 turned out to be several thousand miles away from Latin America or Asia. Warning in January 2010 that heavily indebted eurozone states lacked the flexibility of an independent monetary policy, The Banker spoke to the architects of past fiscal adjustment programmes, such as those in Sweden or Canada in the 1990s. Suggested lessons included thinking deeply about the functions of government rather than setting arbitrary budget cutting targets, and ensuring a sense of national purpose across the political spectrum to establish broad popular support for fiscal adjustment. We leave it to the reader to assess whether the eurozone response has measured up to those criteria.

One other insight gleaned from these pages is that history is very much in the eye of the beholder. One of the most contentious products of the Wall Street crash was the Glass-Steagall reform embodied in the banking act signed into law in June 1933. The two policy-makers’ names have become synonymous with the separation of commercial banks and brokerages, a legal requirement finally overturned by their successors in the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, which this magazine described as “bowing to the inevitable”.

“The financial services market has changed out of all recognition since the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, under which banks and securities firms were kept separate. In the absence of a reform, regulators developed rules allowing banks to do some securities business almost haphazardly,” The Banker observed in December 1999.

Yet in 1933, the bank/brokerage separation prompted barely a mention in the magazine, with many words devoted instead to the creation of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). That coverage serves as a salutary reminder that bankers tend to exhibit hostile reactions (perhaps overreactions) to any new piece of government legislation. The American Bankers’ Association pronounced the idea “unsound, unscientific, unjust and dangerous”, while bankers in New York foretold dire consequences to the magazine’s correspondent.

“Some of the important State-chartered member banks of the Federal Reserve in New York City are seriously considering attempting to withdraw from the Federal Reserve System if the bill is enacted. They have, however, little illusions that they would be allowed by Congress to withdraw and one or two of these banks have even gone so far as to discuss the possibility of winding up their affairs rather than to continue operations under what they consider a menace to themselves and their depositors.”

Needless to say, Wall Street did not simply close its doors, the FDIC is today considered a vital foundation stone of US financial stability, and the author of this month’s Bracken column calls for the establishment of an equivalent institution for the eurozone. The 1933 warnings of banks abandoning the market sound eerily contemporary. In November 2015, a representative of the largest broker-dealers warned one of our correspondents on the subject of regulatory change: “At some point, we need to think about where this will leave the industry when it comes to serving the real economy.”

Changing role of central banks

Today’s debates about quantitative easing and the European Central Bank’s steadily increasing involvement in eurozone bond markets are, of course, just the latest in long-running discussions on the role of central banks within the financial system. The euro is something of a throwback in the sense that, for most of this magazine’s history, defending fixed exchange rates has been one of the most defining (and challenging) roles of a central bank.

The first (failed) defence occupied the lead article of the October 1931 edition – sterling’s fall from the gold standard. The gold standard stopped frequent temporary fluctuations in exchange rates, The Banker suggested. “But if the demand is all one way for a long time, the Bank of England will first of all lose all its gold, and finally the gold standard will break down.”

This is not to say that the magazine disapproved of the gold standard. Far from it. Without the gold standard, central banks are not issuing currency against gold, but “against hope and expectation that one day the Government will be able to redeem it. Issue of fresh currency under these circumstances can only have one consequence. It leads to the depreciation of the national currency.”

As late as 1967, when the UK devalued sterling, the importance of fixed exchange rates was not in doubt. Assessing whether the US dollar would be forced to follow sterling, The Banker noted that this proposal had been made repeatedly by one congressman. “US official circles are quite confident that no such radical remedy will be needed. In the last analysis, the ultimate defence lies in the common interest shared by the central bankers in maintaining international financial stability.”

Yet just four years later, US president Richard Nixon left the Bretton Woods system on the brink in August 1971, by ending the gold convertibility of dollars. Months of negotiations persuaded the US to restore a link between the dollar and gold, but this only lasted until February 1973.

In September 1971, The Banker acknowledged that “there is much academic support for fully floating exchanges unfettered by any fixed rate”, and that “a return to rigidly fixed national parities is now improbable”. Nevertheless, the editorial leaned toward continued linkages between exchange rates, but with much wider trading bands than in the original Bretton Woods system.

While developed markets drifted away from fixed exchange rates against gold during 1973, emerging markets increasingly adopted fixed parities against the dollar to promote financial stability. This model was thrown into doubt by the Latin American crisis in the 1980s, but persisted into the 1990s. By the time of the Asian crisis in August 1997, The Banker’s view of fixed exchange rates was unequivocally negative.

“For developing countries to pursue currency stability at the expense of export competitiveness is to court disaster; and the whole issue of capital market freedoms in such countries needs serious rethinking,” the magazine concluded.

The euro’s long march

What then to make of the rebirth of a new fixed exchange rate system – the euro – in the 1990s? Already in the wake of the gold standard collapse of 1971, The Banker expressed support for professor Karl Schiller’s proposal to link the exchange rate of what were then called the Common Market currencies. The route from there to the euro was fraught with difficulty, most notably the collapse of the exchange rate mechanism (ERM) in 1992. Eschewing its own editorial stance, The Banker asked four bankers, and the subject divided opinion every bit as sharply as it does today.

“Should sterling be sidelined on the route to monetary union, then this will leave British industry at a serious cost disadvantage to its major competitors, and may relegate the UK financial sector as a whole to the minor league,” fumed Lord Younger, then chairman of RBS. By contrast, Abbey National chief executive Peter Birch expected the decision to herald economic recovery.

“Sterling’s exit from the ERM should return control of monetary policy to the government, enabling it to take decisions on interest rates with more emphasis on domestic needs than on supporting sterling in the ERM,” said Mr Birch.

On one aspect of central banking, however, The Banker’s global remit has yielded an unwavering editorial line: the need for international co-operation. This point was rammed home as the gold standard unravelled in 1931.

“The main lesson of this very regrettable episode is that if central bank co-operation is to be a success, more is required than joint action and decision upon broad lines. Representatives of central banks must learn each other’s practices and traditions, must be prepared to discuss and agree upon points of detail, must even get inside each other’s skins,” noted an editorial.

In this edition, you can read a strikingly similar view in the context of developed market zero interest rate policies from Jaime Caruana, general manager at the Bank for International Settlements – an institution just four years younger than our venerable magazine.

Tech pioneers

Banking executives are quick to emphasise the importance of technological innovation, but in the early days, technology was to be found not so much in the articles as in the advertisements: telephone exchanges, lifts, and safes capable of resisting the attentions of an oxy-acetylene lamp. Little wonder that Bracken chose to run a feature on modern strong-room designs in December 1926, which attracted a healthy set of associated advertising.

In August 1929, a breakthrough. H L Rouse, the assistant chief accountant at Midland Bank, wrote a feature on mechanical accounting and its effects. The new ledger-posting machine with a tally roll was “revolutionary”. It would help bring down costs “that have long been rising disproportionately to earnings”. The reliability of book-keeping was also greatly improved. So what were the drawbacks? The “displacement” of male staff, partly offset by new branch openings and “the engagement of a few additional lady clerks”.

All in all, the magazine concluded, mechanisation was “gradually emancipating the world from the age-long thraldom of routine drudgery”. Older clerks might fear it, but a new generation would be “enabled at an earlier age to grapple with the more technical tasks of the profession”.

More than five decades later, sixth editor Colin Jones launched a dedicated technology section, entitled “Banking Tomorrow”, with a feature in January 1983 on the birth of something called home banking. The Homelink system was a remarkable coup for the Nottingham Building Society, with assets of just £170m and 150,000 customers. It used the pre-home computer Prestel Viewdata system of British Telecom – then a state-owned monopoly.

Inevitably, the big beasts of banking soon adopted the idea. But the Nottingham, founded in 1849, remains today one of the UK’s much-reduced cohort of independent building societies. The latest generation of technology-driven upstarts looking to challenge the high street brands will no doubt hope for similar longevity.