One of the biggest unresolved issues in global financial markets is the difficulty small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) typically have when it comes to accessing finance. Insufficient collateral, poor or non-existent credit histories and sometimes a lack of knowledge are just some of the reasons why traditional financial institutions are not catering for small businesses.

Now tech giants in the shape of e-commerce or digital payments platforms have started lending to SMEs. To do this they are using enormous amounts of proprietary data on their users to assess risk in new ways – something banks cannot do. Amazon or PayPal in the West and digital platforms such as China’s Alibaba already have lending arms that are targeting small businesses.

But can technology alone bridge the SME financing gap? Many market participants believe that this will only be possible if today’s trade ecosystem and financial regulation evolve to keep up with technological change.

Bridging the gap

According to an Asian Development Bank (ADB) survey, today’s trade finance gap stands at $1500bn, based on rejection rates for trade finance transactions reported by banks. SMEs and midcap firms account for three-quarters of these rejections. What is more, about 60% of the firms responding to the survey said that after their application for trade finance was rejected, it meant they lost trade.

“On an aggregate level, that is a huge drag on economic growth,” says Steven Beck, head of trade finance at the ADB. Job creation is also affected by lack of credit. “If we were able to provide just 10% more trade finance, companies would be able to employ 1% more staff on a macro level. That is significant,” adds Mr Beck.

It is widely recognised that technology is now crucial in bridging this gap. Tech giants have begun helping small businesses to go global – as well as the likes of Amazon, PayPal and Alibaba, e-commerce platform eBay trains and advises small businesses to help them increase trade.

“From introductory training and start-up advice for new entrepreneurs, through to export guidance for more established businesses, we partner with businesses of all sizes to help them succeed,” says Kris Beyens, chief operating officer, Europe Middle East and Africa, at eBay. “We are looking more and more at the added value eBay can bring to sellers by working with partners in the shipping and financial sectors.”

Amazon and PayPal have a different strategy, both establishing lending arms that target their own users. In June 2017, Amazon announced that it had lent more than $3bn to small businesses across the UK, the US and Japan since launching Amazon Lending in 2011. One-third of this was in the 12 months to June 2017, and so far Amazon has extended loans to more than 20,000 small businesses.

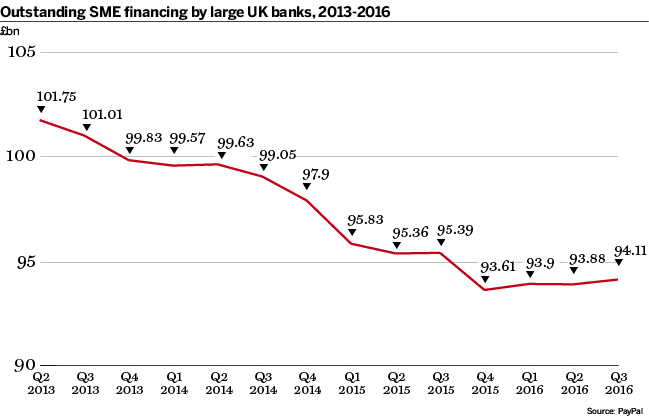

PayPal has also reached the $3bn SME financing mark – and in less time. It launched lending arm PayPal Working Capital in the US in 2013, and in the UK and Australia in 2014. The company has to-date financed a total of 115,000 businesses.

PayPal makes friends

As an online payments system that works with e-commerce platforms such as eBay, PayPal has precious insight into its users. “As a closed-loop environment with relationships with merchants and sellers, we have tremendous information on small businesses,” says Norah Coelho, director of PayPal Working Capital UK.

While in the US and Australia PayPal Working Capital offers business loans, in the UK the payments firm offers merchant cash advances or a lump sum that businesses pay back by forgoing a set percentage of every PayPal sale, plus a fee. “What is unique about it is the repayment profile flexes with customer sales. When sales are slower, repayments flex accordingly. For small business owners that have challenges in forecasting cash flow, this is a more flexible product versus bank term loans or credit cards that require fixed or minimum monthly payments,” says Ms Coelho.

In addition, the minimum size for tech firms’ loans or cash advances tends to be smaller than bank loans – for example, Amazon loans start at $1000. PayPal’s UK cash advances start at £1000 ($1350), while loans in Australia and in the US start at A$1000 ($800) and $1000, respectively.

Applying to tech firms for credit is also relatively quick. While securing a bank loan can take up to a month, small businesses often have almost immediate access to finance once their application to digital platforms is successful. “Even [the] larger SMEs tell us they don’t want to spend time pulling together paperwork, making an appointment and going to see a loan officer. The ability [for them] to have a tech-enabled experience is really powerful,” says Ms Coelho.

What is more, accessing bank branches is becoming harder as most incumbent banks are reducing their physical branches to cut costs. Indeed, one-third of PayPal Working Capital cash in the UK has gone to businesses registered in areas that have lost 50 or more bank branches in the past four years.

Fintech threat?

The reaction of banks to tech firms financing SMEs differs. “We take it very seriously. There are many players, for example small fintech companies, getting a small piece of the business,” says Bernd Laber, global head of trade finance and cash management at Commerzbank. “But of course we co-operate with technology firms and fintechs in various projects – that’s the future.” The German lender is collaborating with the Fraunhofer Institute for Material Flow and Logistics on applying blockchain technology to supply chain finance.

Other bankers are more dismissive of the fintech threat, however. “People talk about Alibaba or Amazon as if it’s a new thing,” says Michael Vrontamitis, global head, trade products and transaction banking, at Standard Chartered. “[General Electric] set up its own financing arm in the 1970s. Siemens has one too. Banks have been financing large corporates to enable them to finance their own clients since the dawn of time.”

The ADB survey also shows that most companies surveyed still relied on banks as their key source of financing, while about 38% of firms that used fintech solutions also received bank finance.

Banking options

One of banks’ competitive advantages over tech firms is the broad range of financial products they can offer. While tech giants tend to be involved in straightforward lending, which small businesses use as working capital, banks also provide traditional trade finance. Digital platforms’ lending strategy is such because e-commerce transactions tend to be small, low-value shipments and do not require trade finance.

But is there a chance tech giants will expand into trade finance or acquire full banking licences? Mr Vrontamitis is sceptical. “Do tech giants want to put the capital on the table, engage in all the regulations [the banks engage with] and reduce their [price/earnings ratio] and shareholder value? The answer is probably no,” he says.

However, Arancha Gonzalez, executive director of the International Trade Centre, disagrees. “It is only a matter of time before tech giants realise there is space to grow in SME trade finance. They have [access to such] track records and behavioural history of so many customers that they could get into trade finance,” she says.

While tech giants in China are acquiring banking licences, this is not always the case in the West. PayPal, for instance, is licensed as a Luxembourg credit institution and passports this licence into the UK. But since the UK voted to leave the EU, it is unclear whether the British market will retain passporting rights. “This is a topic we are very focused on. We will ensure continuity in our business in the UK and all over the EU. We are evaluating all scenarios and will ensure we can continue to operate our business in the future,” says Ms Coelho.

Meanwhile, PayPal’s lending arm is growing. The firm announced it would acquire Delaware-based Swift Financial, which provides working capital to small business owners. “We see an opportunity to complement the business we have built with new products and Swift Financial’s underwriting expertise,” says Ms Coelho. PayPal Working Capital is also considering expanding into new markets, but has no set expansion plans.

Is tech the answer?

While tech firms’ SME financing is on the rise, some market participants argue that technology still is not making a significant impact on the global financing gap. “There is no evidence to support the idea that fintech is reducing the SME financing gap. There is no question, [however,] that it’s reducing the cost of financial institutions to deliver products,” says the ADB’s Mr Beck. In the ADB 2017 survey, only 20% of firms used digital finance platforms.

One problem is that tech giants have not entered the developing markets that have the greatest need for SME financing. With the exception of China, these platforms still mainly target the UK and the US. However, at 40%, it is the Asia-Pacific region that accounts for the biggest proportion of the global financing gap registered by the ADB.

“There may be a need to incentivise financial institutions and tech companies to move into developing markets. Development aid could make a first move, [and provide] a downpayment or derisking,” says Ms Gonzalez.

The large digital platforms also tend to finance young, tech-savvy businesses and start-ups rather than the older SME sector that struggles the most to secure credit. And although tech giants are catering to small businesses, their lending comes at higher rates. “A number of hedge funds that invest in some [online lending] platforms look for 8% to 9% returns to cover potential losses,” says Mr Vrontamitis.

More broadly, Mr Beck cautions against today’s fintech hype. “In the past two years there has been so much investment in fintech and lots of proof of concepts [PoC]. But when you look at the number of PoCs that actually got mainstreamed, it’s negligible. There is a lot of work to be done before the hype and excitement meets the real world,” he says.

Digital standards

Indeed, while technology has generated new and cheaper ways of assessing risk, this is not enough to plug the financing gap, as today’s financial ecosystem is still built largely to support traditional forms of credit and trade. Market participants believe building standardised directives on digital transactions and reforming financial regulation are both crucial to fulfil technology’s potential to ensure SMEs get the trade finance they need.

Interoperability is a key issue. The trade finance business is digitising, and third-party platforms monitoring supply chains give banks more visibility on trade transactions. However, these platforms remain fragmented. “They don’t speak to each other so you cannot get the full picture,” says Mr Vrontamitis.

Ideally, banks would like to trace a transaction from the consumer throughout the whole of the supply chain. “You can then start looking at real-time credit analysis and understand how the risk profile of the transaction changes. But at the moment, risk assessment is done at company level, not at transaction level, and it is based on backward-looking factors,” says Mr Vrontamitis. This is partly why SMEs struggle to secure bank loans in that they tend to have unregistered or poor credit histories.

What is more, trade finance is still heavily paper based – which many believe will never change. But, says Mr Beck, no technological advancement will fulfil its potential unless all components of a transaction become digitised. “Common technical standards need to be sorted to address the fundamental problem of interoperability. And industry, finance, customs, logistics and shipping have a long way to go on the digitisation front,” he adds.

Setting up directives for digital transactions is key to this process but this is not easy. There are no reference points to work from and the process requires “a full and transparent dialogue with everyone involved to reach operational guidance and rules”, says Olivier Paul, head of policy at the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) banking commission, which drives policy dialogue on the subject. “The first step is to define exactly what a digital transaction is. Then we can move on to establishing rules for monitoring those transactions,” he adds.

Collateral obsession

A second reform that would help plug the SME financing gap involves banks’ risk assessment methods. While digital platforms assess SME risk by looking at e-commerce sales, mobile phone usage or shipment timings, banks still put large emphasis on collateral, which SMEs tend to lack.

Part of the problem is bank regulations. “We have a bit of a disconnect between know your customer [KYC] requirements and what technology allows us to know about customers through other means. Regulation is still playing catch up,” says Ms Gonzalez.

The crux of the matter is that regulators treat trade finance risk “the same way as other financial instruments that, frankly speaking, are a bit more toxic,” she adds. “Trade finance default rates are minimal. There is a concerted effort to get financial regulators to recognise that trade finance is not such a risky financial instrument.”

New identifier systems

In addition, market participants are calling for a standardised identifier system for companies worldwide. This assigns firms a unique ID number linked to a database of information that financial institutions can use for due diligence. Such a system could dramatically increase the visibility of SMEs’ performance.

But building this kind of system is tricky considering not even the EU has a standardised identifier methodology. “The issue is determining which [regulation] has jurisdiction: EU or local regulation,” says Mr Paul.

In fact, a global identifier system already exists. The Global Legal Entity Identifier Foundation (GLEIF), set up by the Financial Stability Board in June 2014, is a database for legal entity identifiers (LEI), a 20-digit number assigned to any legal entity involved in a financial transaction.

The problem is that not all countries are adopting GLEIF. “The holy grail for driving global adoption… is to convince all governments to legislate a requirement for companies to acquire an LEI connected with GLEIF,” says Mr Beck. “G20 countries could be a starting point since GLEIF was the brainchild of the G20.”

But to drive adoption there first needs to be a general consensus on what should be included in a database, and this will take time, according to Mr Paul. “This is a global initiative that could be led by institutions such as the UN,” he says. The ICC could drive this dialogue after becoming the first business organisation to obtain observer status at the UN General Assembly in December 2016.

KYC costs

Initiatives such as GLEIF are essential because they could help cut KYC costs, which are as high as $30,000 for a single counterparty. Banks often do not think this is worth it for small businesses. “The reluctance to undertake due diligence on SMEs is related to low expected revenue. Unlike the case for large corporates, SMEs’ trade transactions are often small, and the trade may not be repeated,” says Alisa Di Caprio, research fellow at the ADB Institute.

“If the business and the relevant financing is too small, there can be limitations in supply chain finance because the entire KYC process can become overwhelming,” says Commerzbank’s Mr Laber, while Standard Chartered’s Mr Vrontamitis says: “If we went out and tried to finance a whole bunch of SMEs, we would probably make the wrong credit decisions. We would probably end up with a bloated balance sheet and lose money.”

According to Ms Gonzalez, banks’ perception of SMEs is misguided, as in the short term they see financing SMEs as taking more effort and generating little profit. “[But] if you take the medium- to long-term view, you have a huge unexploited market that you are not profiting from just because you don’t want to make an investment,” she says. “Banks need to take the long-term view and not be bothered by short-term impacts on their balance sheet. Otherwise we will continue to have a $1500bn financing gap.”

Meeting in the Mittelstand

While it is true that banks have historically underserved SMEs, not everyone has shunned small businesses. In Commerzbank’s case, servicing German SMEs, collectively known as the Mittelstand, is at the core of its strategy. “In Germany, if you want to be a top corporate bank, you need to serve SMEs,” says Mr Laber.

Commerzbank also serves German SMEs abroad to help them go global. Today, Mr Laber sees strong potential along China’s Belt and Road initiative, especially in central Asian markets, where Commerzbank has operations. “Very few banks have representative offices in these countries [such as Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Armenia]. We have the local expertise and risk management capacity to take risk… because we have a local presence,” he says.

Commerzbank’s representative offices have credit lines with local banks, meaning that when opening an export letter of credit, for instance, it can take the risk off the exporter through the importer’s bank. In Europe, Commerzbank even services domestic SMEs in Switzerland since no Swiss bank focuses on supporting small businesses’ international operations, despite strong exports and foreign direct investment in the country.

While Commerzbank stands out for its commitment to SMEs, it is fair to note that the Mittelstand tend to be sophisticated firms with strong balance sheets that do not require complex due diligence. “The German Mittelstand are very bankable,” says Mr Laber.

Tech giants are providing working capital to small businesses starved of credit, while smaller fintech companies are revolutionising the trade finance business. But fundamental shifts in financial regulation and the global trade ecosystem still need to accompany these new trends if technology is to meaningfully address the SME financing gap.